Logical Fallacies in IC3 Reports: Analysis of Statistical Manipulation

Scrutinizing Business Email Compromize (BEC) Crime Resolution Statistics (2023)

Purpose

Before delving into the analysis presented in this article, I want to emphasize my deep respect and appreciation for the dedicated special agents of the FBI, assistant U.S. attorneys, and all law enforcement professionals who have devoted their lives to pursuing justice and protecting victims of crime. Over the years, I have had the privilege of working closely with hundreds of law enforcement agents in many countries, including many from the FBI and other Department of Justice agencies. My experiences with these committed professionals have been immensely rewarding, and I hold their work in the highest regard.

The critiques and observations contained herein are not directed at these hardworking individuals, who often operate under immense pressure and with limited resources in their tireless efforts to combat cybercrime. Instead, this analysis focuses on the statistical presentation within the 2023 IC3 report, as prepared by the analysts responsible for its compilation. The goal is to highlight potential areas of improvement in how data is reported and interpreted, ensuring that both law enforcement and the public can have a clearer understanding of the challenges and successes in the ongoing fight against cybercrime.

Accurate and transparent reporting is essential for building trust between law enforcement and the public, and for setting realistic expectations for victims of cybercrime. Many victims place significant trust in traditional law enforcement’s ability to address their cases, often filing reports with agencies like ic3.gov in the U.S., or equivalent portals in other countries, expecting not only a response but a successful resolution. Reports like the one critiqued herein can unintentionally fuel these expectations, leading to disappointment and despair when cases go cold.

This article aims to shed light on how statistical presentations in crime reports can sometimes create a skewed perception of success, and why it is crucial for all stakeholders—law enforcement, victims, and the public—to have a clear, accurate understanding of the challenges at hand. By addressing these issues, we can work towards more effective strategies in the fight against cybercrime.

I’ll mash up a quote from Morpheus in The Matrix: Statistical reports are often “the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth”.

I hope my article will catch the attention of mission-driven law enforcement officers (LEOs) in federal, state, County and local law enforcement agencies who know exactly what I'm talking about, join us in an ambitious new public private fusion partnership called "STINGFORCE”. To quote Morpheus again (with another modification), we want to hear from you if:

"What you know you can't explain, but you feel it. You've felt it your entire life (career), that there's something wrong with the world (MLAT delays and career-focused prosecutors). You don't know what it is, but it's there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad."

But we need to be careful, we need to set healthy boundaries between us and the institutionalized LEOs and prosecutors who are perfectly happy with the current status quo, or are intimidated by the passion and efficacy of professional, non-government crime fighters such as fraud and AML analysts, private investigators and anti-trafficking NGO workers. Click the image to join our waiting room:

Common types of logical fallacies used in statistical reporting

Identifying logical fallacies in statistical and government reports is crucial for readers to fully understand the information presented. Logical fallacies, whether intentional or accidental, can distort data interpretation, leading to a misleading portrayal of reality. Common fallacies include cherry-picking data, where only favorable statistics are highlighted while inconvenient ones are ignored; misleading averages, which obscure significant outliers or variations; and confusing correlation with causation, where relationships between variables are wrongly implied as causal. Overgeneralization from limited data and presenting false dilemmas by oversimplifying complex issues are also common tactics. By recognizing these fallacies, readers can critically assess the arguments and conclusions, ensuring they are not swayed by flawed reasoning, and enabling them to make well-informed decisions based on accurate interpretations of the data.

FBI’s 2023 INTERNET CRIME REPORT

Business email compromise section (Pages 9-11)

Misleading Statistics to claim a “71% success rate”

Original reference source document :

https://www.ic3.gov/AnnualReport/Reports/2023_IC3Report.pdf

Fallacy Explanation: Misleading statistics, or “cherry-picking”, occurs when data is selectively presented to support a particular conclusion while ignoring other data that may contradict it. The following analysis could also be described as a "faulty sample”

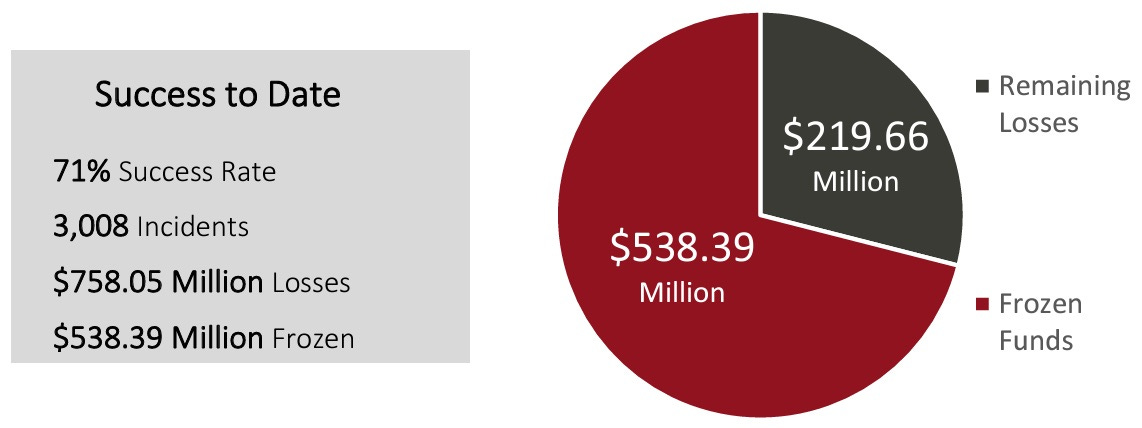

Application of this logical fallacy in the IC3 2023 Report: The FBI report highlights a special unit called “The Internet Crime Complaint Center’s Recovery Asset Team (RAT)”. The report claims that the RAT team achieved a “71% success rate” and emphasizes the total amount of money frozen ($538.39 million) compared to the total reported losses ($758.05 million). By focusing on these success metrics, the report potentially downplays the total number of unresolved incidents and the amount of money not recovered.

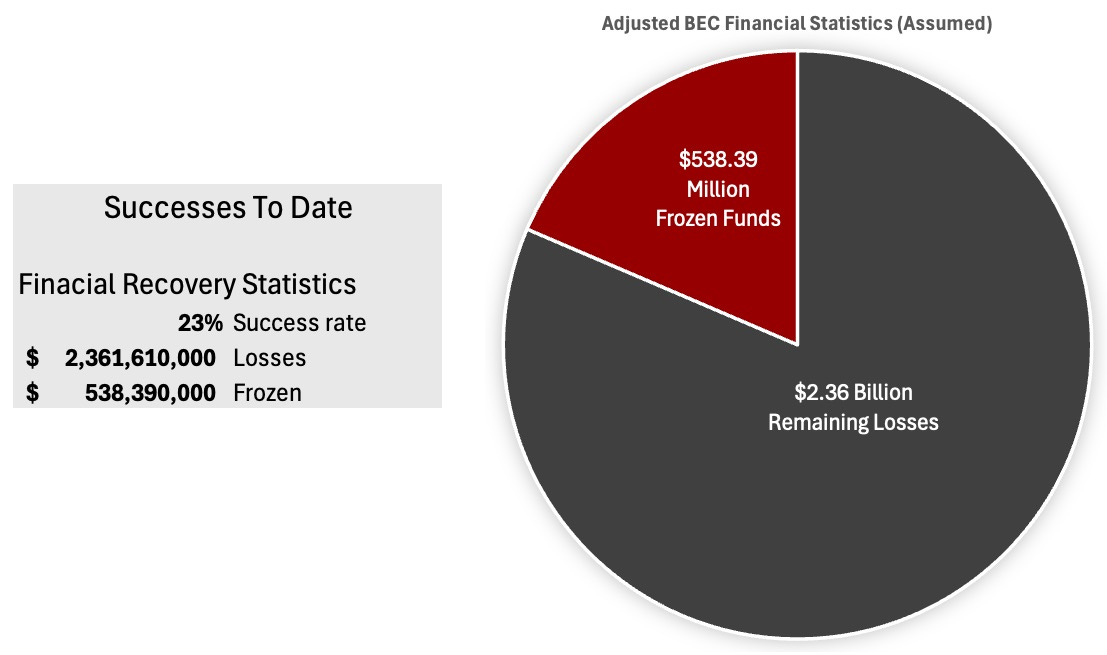

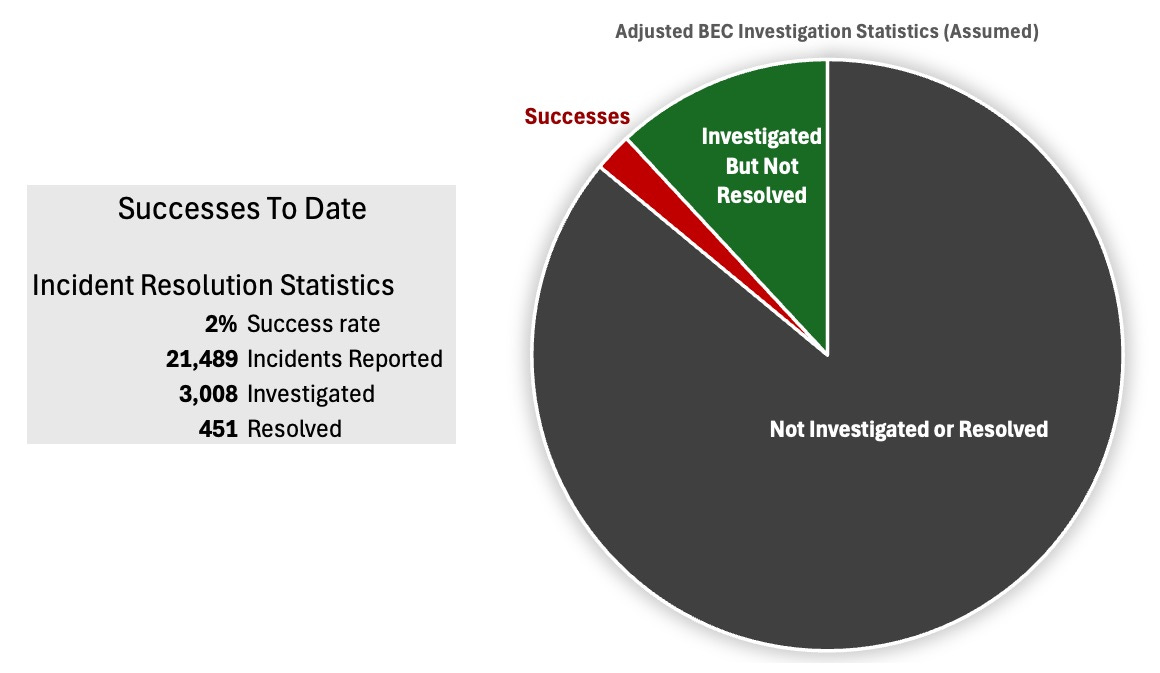

WHEREAS: In reality, the 3,008 cases referred to the RAT team represent just 14% of the 21,489 total BEC incidents reported to IC3 in 2023. The broader scope of the problem is largely overlooked, as it is not accompanied by detailed graphics, pie charts, or comprehensive outcome statistics. The omission of this crucial information significantly downplays the severity of the BEC issue, highlights law enforcement’s challenges in addressing it, and underestimates its impact on the business community.

Page 11 excerpt:

2023 OVERVIEW BUSINESS EMAIL COMPROMISE (BEC)

“In 2023, the IC3 received 21,489 BEC complaints with adjusted losses over 2.9 billion. BEC is a sophisticated scam targeting both businesses and individuals performing transfers of funds. The scam is frequently carried out when a subject compromises legitimate business email accounts through social engineering or computer intrusion techniques to conduct unauthorized transfers of funds.

These BEC schemes historically involved compromised vendor emails, requests for W-2 information, targeting of the real estate sector, and fraudulent requests for large amounts of gift cards. More recently, the IC3 data suggests fraudsters are increasingly using custodial accounts held at financial institutions for cryptocurrency exchanges or third-party payment processors, or having targeted individuals send funds directly to these platforms where funds are quickly dispersed.

With these increased tactics of funds going directly to cryptocurrency platforms and third-party payment processors or through a custodial account held at a financial institution, it emphasizes the importance of leveraging two-factor or multi-factor authentication as an additional security layer. Procedures should be put in place to verify payments and purchase requests outside of email communication and can include direct phone calls but to a known verified number and not relying on information or phone numbers included in the email communication. Other best practices include carefully examining the email address, URL, and spelling used in any correspondence and not clicking on anything in an unsolicited email or text message asking you to update or verify account information.”

When adjusting for reality, how does it look?

Because no overall statistics were provided, I have had to make quite a few assumptions (guesses), these can be adjusted if a FOIA request that I intend to submit receives a response.

My assumptions:

The only significant recoveries made were by the RAT team, as reported in the report’s case highlights.

There were no (zero) recoveries outside the RAT team; or were so statistically insignificant that inclusion in the overall report was not warranted.

There were no BEC crime investigations outside the RAT team (which is unlikely), or were so statistically insignificant that inclusion in the overall report was not warranted.

Of the 3,005 BEC reports referred to the RAT Team, 100% were investigated (unlikley).

Of the 3,005 BEC reports referred to the RAT Team, only 10% of the cases had successful financial recoveries (a generous assumption).

My assumptions do not include the likelihood that as few as 10% of Cybercrimes are actually reported to law enforcement, as many experts posit:

“Cybercrimes are vastly undercounted because they aren’t reported — due to embarrassment, fear of reputational harm, and the notion that law enforcement can’t help (amongst other reasons). Some estimates suggest as few as 10 percent of the total number of cybercrimes committed each year are actually reported”.

https://www.nist.gov/press-coverage/2022-cybersecurity-almanac-100-facts-figures-predictions-and-statistics

The following screen capture is from the report:

RAT SUCCESSES

My Adjusted Loss Recovery Statistics (with assumptions)

My Adjusted Case Resolution Statistics (with assumptions)

Other Compounding Logical Fallacies used in the 2023 IC3 BEC Report

Hasty Generalization:

Fallacy Explanation: Hasty generalization involves making a broad conclusion based on a small or non-representative sample of data.

Application in Report: The report provides detailed examples of successful interventions (New York and Connecticut cases) but does not mention the overall number of cases where funds were not recovered or the success rate across different types of cybercrimes. This could lead some readers to generalize these successes to many or most cases, which is not accurate.

Survivorship Bias:

Fallacy Explanation: Survivorship bias occurs when conclusions are drawn from an incomplete set of data because only successful cases are considered.

Application in Report: By only presenting cases where the RAT successfully froze and recovered funds, the report may create a skewed perception of the team’s effectiveness. It fails to mention the number of incidents where no funds were recovered or the specific challenges faced in those cases.

False Cause (Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc):

Fallacy Explanation: a Latin phrase meaning “after this, therefore because of this.” The phrase expresses the logical fallacy of assuming that one thing caused another merely because the first thing preceded the other.

Application in Report: The report implies that the establishment of the RAT directly results in the high success rate and the substantial amount of funds frozen. However, it does not provide a clear causal link or discuss other factors that might contribute to these outcomes, such as increased reporting or improved cooperation from financial institutions.

Fallacy of Incomplete Evidence (Selective Reporting):

Fallacy Explanation: This fallacy occurs when only certain pieces of evidence are presented, while other relevant information is omitted.

Application in Report: The statistics and success stories provided in the report are selectively chosen to highlight positive outcomes. There is a lack of information on the total number of complaints received, the variety of cybercrime types, and detailed breakdowns of unsuccessful recovery or prosecution attempts.

Summary

The FBI’s IC3 report employs several logical fallacies to paint a more favorable picture of its efforts in combating cybercrime. By selectively presenting successful cases, emphasizing high success rates without context, and relying on its authoritative status, the report may obscure the true extent of cybercrime challenges and the overall effectiveness of law enforcement responses. This statistical manipulation can mislead stakeholders into believing that the situation is under better control than it might be, potentially affecting funding, policy decisions, and public perception.

UPDATE (31 Oct 2024)

A recently retired Supervisory Special agent from the FBI emailed me after reading this report, and he added the following important context:

“…from my experience, iC3’s Recovery Asset Team (RAT) identifies complaints involving fraudulent transfers that occurred within 72 hours, which may explain the limited number of 3,008 cases they reported. RAT then uses the FBI’s Financial Fraud Kill Chain (FFKC) to recover those transfers, then refers the case to the respective field office. Transfers over 72 hours have a much lower recovery rate using the FFKC and are usually just referred to the respective field office, which may or may not open a case (but usually doesn’t). Field offices may also do their own recoveries using the FFKC, which I’ve personally done, and then file an iC3 report, but those recoveries are not included in the RAT’s statistics.”

Call To Action

Hurting Crime Victims Need You!

Contact me at https://picdo.org/contact/ for more information about joining the STINGFORCE community in the “effective” fight against transnational organized cybercrime, and human trafficking.

If overselling their successes and minimizing their failures is intentional, I wonder what for? Justifying their current levels of funding and manpower? I'd think them being more honest should actually help them get more. They very well know that they're currently under resourced relative to the scale of crime today